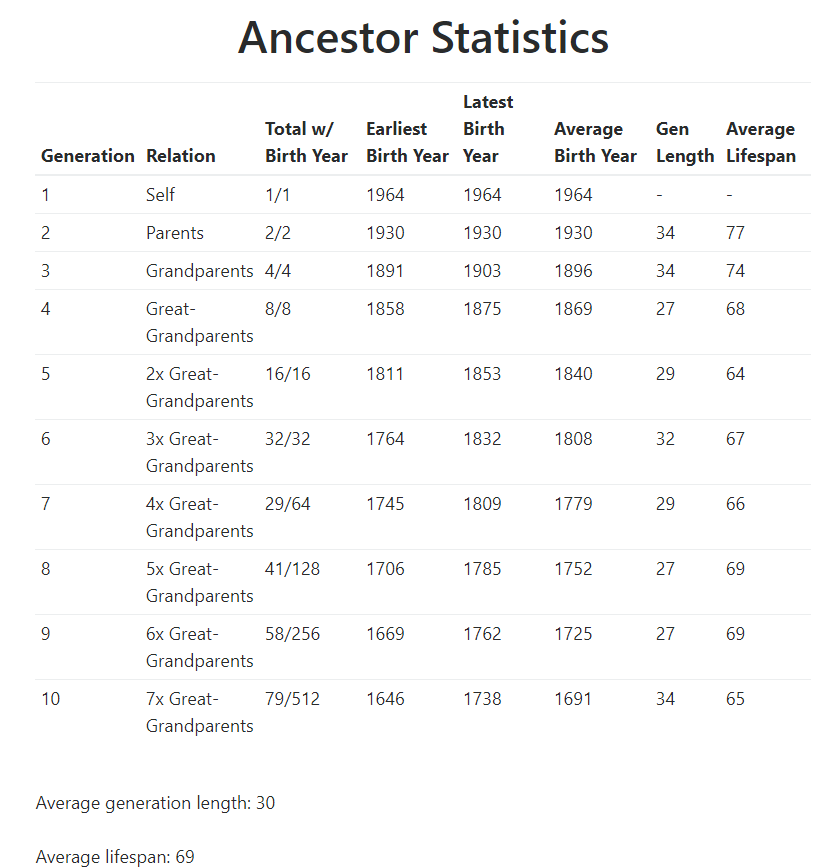

There are a couple of new apps on WikiTree that provide some interesting statistics on your family tree. The first is Ancestor Statistics – if you’re a WikiTree member, go here and log in to see your stats. Here are mine:

I have identified all of my 3rd great-grandparents and have their profiles on WikiTree. After that, it drops off significantly. I only have 45% of my 4th great-grandparents, 32% of my 5th great-grandparents; 22% of my 6th great-grandparents and 15% of my 7th great-grandparents.

The average generation length in my family tree is 30 years. Curious about how that compares to others, I did some google searching and found this article on the International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) wiki that highlights some studies that show generations to be around 25 to 30 years for females and 30 to 35 years for males. So my 30 year average generation length seems about normal.

The average lifespan in my tree is 69 years, and has gone up the last couple of generations, as can be expected due to better health care. For my parents, the lifespan only includes my father’s data (77 years), as my mother is still living and is in her late 80s. My four grandparents lived to 58, 72, 80 and 87, for an average of 74 years. Prior to that, the average ranges from 64 to 68 years. Since to have become my ancestors, each of these people obviously lived to adulthood, it is understandable that the lifespan of my ancestors would exceed average life expectancies for their time periods, since life expectancies take into account people who die in infancy and childhood.

The 2nd app lists all of the profiles in your pedigree chart that are missing at least one parent. You can find that app here.

Find Brick Wall Ancestors

20/400 (5%) are duplicates due to pedigree collapse.

109 ancestors are missing at least one parent:

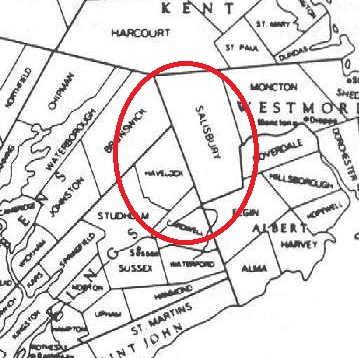

I need to look deeper into the duplicate ancestors in my tree. I can think of a few off hand, but not 20! These are most likely all on my maternal grandmother’s line in Westmorland County, New Brunswick, where everyone’s related to everyone else.

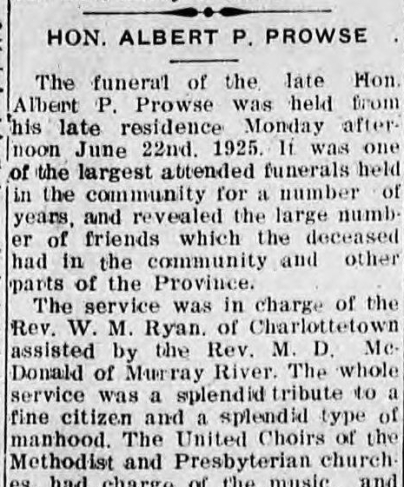

As for brick walls, I am certainly not working on all 109 of them! The main one that I’d like to break through is that of my 3rd great grandparents on my maternal grandfather’s line – John William Kirkland and Elizabeth Weeks. I wrote about my plan to work on that brick wall back in January. I’ve made a bit of progress, but nothing substantial to date. But I’m still plugging away at it, albeit with far less focus than I had hoped for!

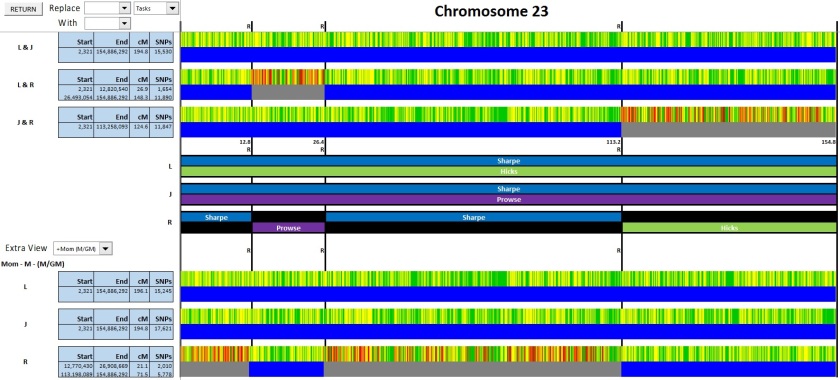

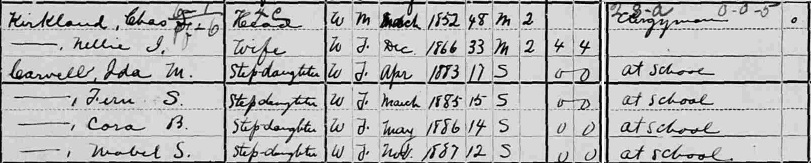

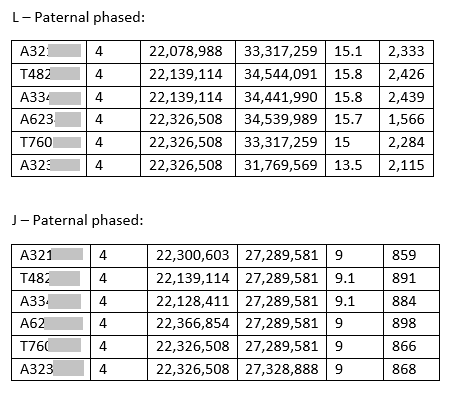

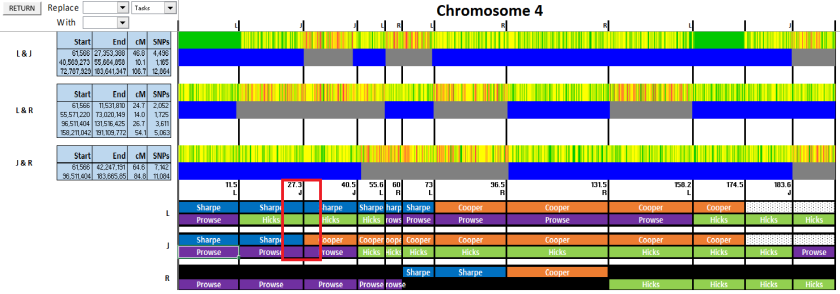

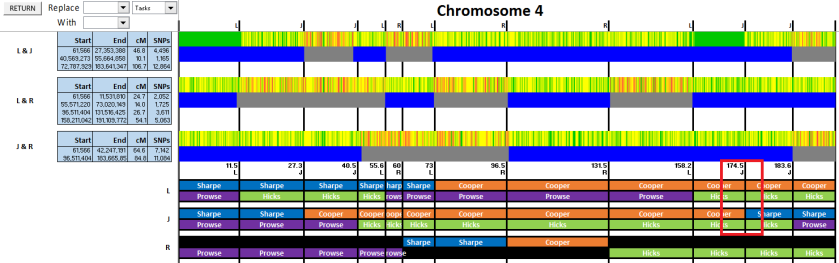

Time to bring in some strangers to help, starting at the crossover on the left, at 27.3 Mb.

Time to bring in some strangers to help, starting at the crossover on the left, at 27.3 Mb. I found 6 people who match L from about 22 Mb to 34 Mb. Those same people match J from 22 Mb to 27.3 Mb. So, even though I have no idea who these matches are (hence the term “stranger matches”), it doesn’t matter. This is enough to tell me that the crossover at 27.3 must belong to J. That enables me to complete the first section.

I found 6 people who match L from about 22 Mb to 34 Mb. Those same people match J from 22 Mb to 27.3 Mb. So, even though I have no idea who these matches are (hence the term “stranger matches”), it doesn’t matter. This is enough to tell me that the crossover at 27.3 must belong to J. That enables me to complete the first section.

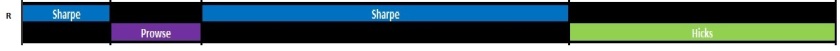

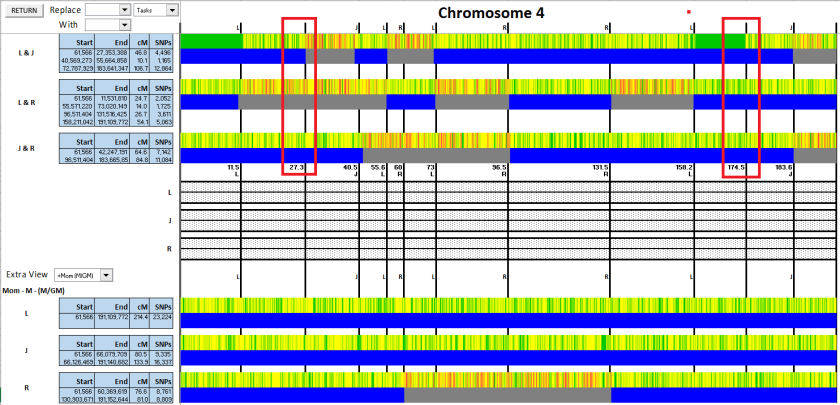

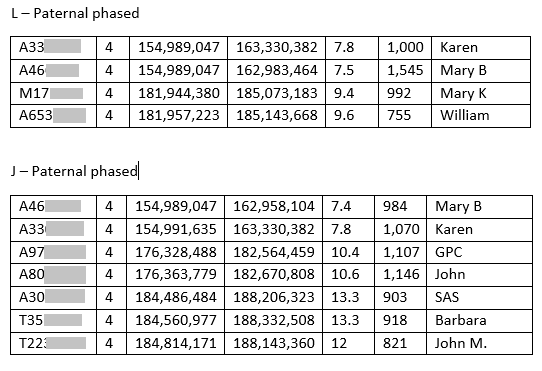

This one is less clear-cut. Neither of us have matches that cross 174.5. We have the same two matches (Karen and Mary B) from 155 Mb to 163 Mb, as expected. And after 174.5, we have different matches, as expected. But who has the Cooper matches and who has the Sharpe matches? To figure this out, I needed to dig into these matches a bit further.

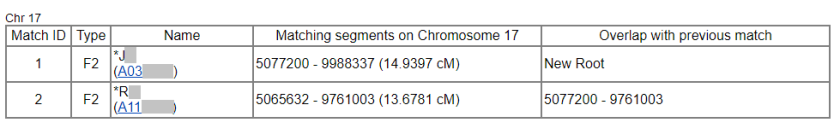

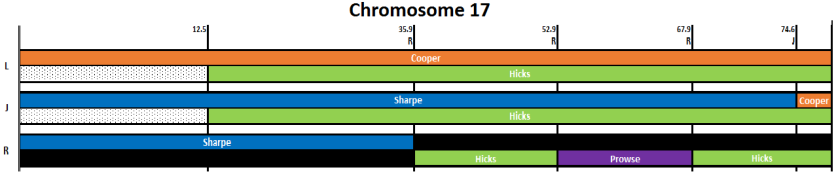

This one is less clear-cut. Neither of us have matches that cross 174.5. We have the same two matches (Karen and Mary B) from 155 Mb to 163 Mb, as expected. And after 174.5, we have different matches, as expected. But who has the Cooper matches and who has the Sharpe matches? To figure this out, I needed to dig into these matches a bit further. Looking at the visually phased Chr 17, John M would appear to be a Sharpe match (paternal grandmother)

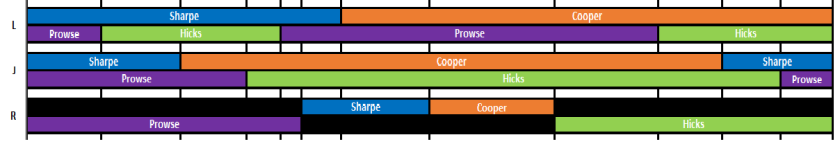

Looking at the visually phased Chr 17, John M would appear to be a Sharpe match (paternal grandmother) As well, I looked up John M in J’s FTDNA matches (his last name appeared in GEDMatch – I removed it for privacy) and found that he has a tree attached to his DNA results. He has ancestors from the same small town in New Brunswick as my grandmother’s ancestors, including one with a surname in that line. Since our paternal grandfather and grandmother came from different countries, it would be highly unlikely that we match on Chr 4 on one line and Chr 17 on a different. And since both segments are of a decent size (12cM and 14.9cM), it’s unlikely that one is a false match.

As well, I looked up John M in J’s FTDNA matches (his last name appeared in GEDMatch – I removed it for privacy) and found that he has a tree attached to his DNA results. He has ancestors from the same small town in New Brunswick as my grandmother’s ancestors, including one with a surname in that line. Since our paternal grandfather and grandmother came from different countries, it would be highly unlikely that we match on Chr 4 on one line and Chr 17 on a different. And since both segments are of a decent size (12cM and 14.9cM), it’s unlikely that one is a false match. And Chromosome 4 is complete

And Chromosome 4 is complete With the help of some stranger matches.

With the help of some stranger matches.